Tees Valley

Mayoral Election:

The Lesson Labour

Didn't Learn

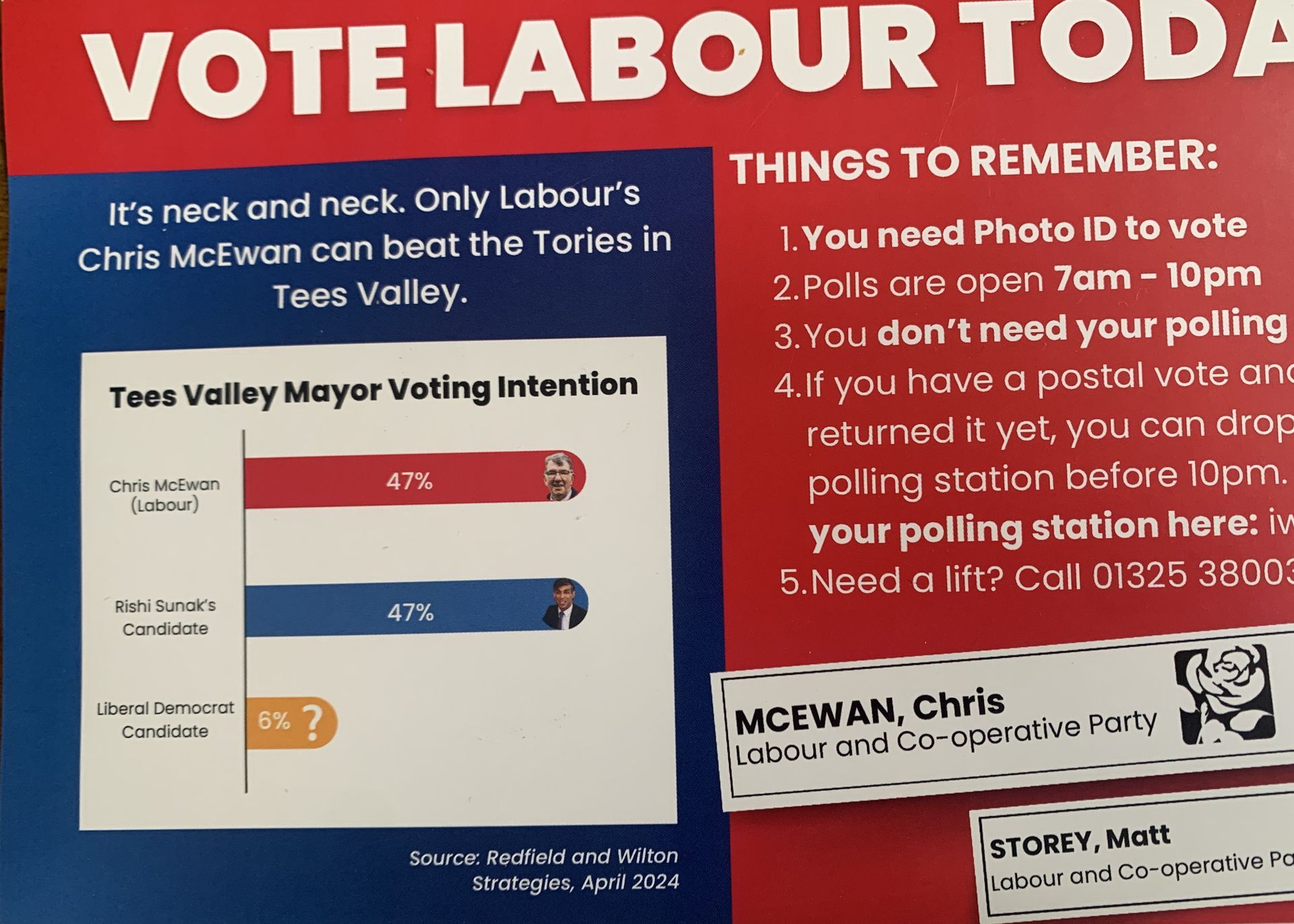

Labour's final election leaflet: witty but inaccurate

Scott Hunter

3 May 2024

We don’t know what Ben Houchen does to relax after a hard day at the election count, but whatever it is, he’s doing it now, having just won a third term in office. It must come as an enormous relief to him as he has clearly been nervous throughout the campaign, from being fractious in a BBC election debate, to loudly, and wholly unnecessarily, distancing himself from the Tories at Westminster, to claiming he would build a new hospital if re-elected event though health is not a devolved responsibility. The nervousness is remarkable for a politician who took 73% of the vote when he was last elected. That, you would think, had to be a mountain for his main rival to climb. Yet Houchen was taking nothing for granted.

For his Labour opponent, the situation was different. He represents a party that is around 20 points ahead in national opinion polls, while the Tories’ projected share seems to be deteriorating by the day. He is an experienced local councillor and is well liked. Moreover, the incumbent’s standing has taken a battering in the years since the last mayoral contest – financial scandal, a serious pollution incident, which despite official denials, is believed by many locally to be linked to ongoing work at Teesworks, an official review into Teesworks and the South Tees Development Corporation in which he was heavily criticized, an enormous bill for court costs following a dispute with PD Ports, and the airport that he brought into public ownership posting huge annual losses. So, for Chris McEwan, it was all to play for. Houchen’s position was not unassailable after all.

And then he lost. And, in fact, party officials were briefing journalists of this almost a week before the election. There was no knife edge. How could it all go so wrong?

To look for answers to that question it is necessary to look at the Labour Party, as this was always their fight much more than it was ever McEwan’s. In essence, what is to be understood is that, despite being damaged goods, Houchen took on the Labour Party and won. Labour is almost certain to win a landslide victory in the forthcoming general election, yet Houchen can beat them.

Labour, in other words, has a problem. Quite a serious one, which, as we have pointed out before (99-Lead-Balloons-Labour’s-Losing-Strategy-for-the-Tees-Valley-Mayoralty), is that it basically just doesn’t get devolution. Which leads us on to the difficult topic of trying to explain why Houchen wins elections.

Deep breath. Here goes.

Ben Houchen: the good bits

We, at Tees Valley Monitor, have been Houchen’s longest-serving critics in the media. That hasn’t changed, and we see every day he continues in office to be another day when public money is squandered, contracts are signed that favour the interests of his associates, the public is insulted with spurious tales of investment and jobs, and anyone who questions him is bullied and intimidated. Houchen, in short, is a liability.

On the other hand, his strategist comes up with a narrative of regeneration and pride in the local area. The fact that the reality on the ground does not match that narrative does not diminish its power. Because Houchen and his strategist have created something that, once unleashed, is self-sustaining. They create expectation, and with that the work of the mayoralty becomes aspirational.

The narrative, particularly in relation to the airport, is then sustained by acolytes who endlessly repeat the slogans – Labour tried to shut the airport and turn it over to housing, Peel ran the airport into the ground, the people’s airport, Houchen saved the airport, investors don’t arrive by bus, and so on.

Any critical voice is accused of ‘talking down Teesside’. Houchen is the dynamic leader who gets things done. This is supported by a constant drip feed of information (or misinformation) giving the public the good news about the progress of the projects and the vast amounts of money Houchen has been able to get his hands on to carry them out.

This then seeps in, much like the narrative put out by Johnson and the Eurosceptics at an earlier date about straight bananas and bonkers Brussels red tape. Long before there’s an opportunity for a vote, millions of people have become ‘informed’ and no longer question the version of events presented to them.

He also speaks only of his own projects and rarely gets involved with politics outside of the region. So, the turmoil in the Conservative Party passes him by. He makes the necessary minimum of comment (he was obliged to acknowledge his allegiance to Johnson, for example), but otherwise stays well out of the way.

So, when comments appear in the press about how Tory local election candidates are avoiding using Party branding on their literature, this is essentially irrelevant for Houchen. He has already created his own identity, and campaigns to promote his brand 365 days a year. In so doing, he has been the main driver in creating the sense of identity of the Tees Valley as a region.

We must give credit where credit is due; Houchen’s strategy is brilliant, it helps him to survive scandal, and it wins him elections. He understands the potential of devolution. That much cannot reasonably be denied him.

Labour: the Dead Hand of Centralism

Come the election, Labour, their candidate steeped in party message discipline, counters Houchen’s vision for the region with a campaign based around capping bus fares and reintroducing free parking in town centres. Flamboyance meets drab.

There’s nothing wrong with these two policies in themselves. They are sound, pragmatic measures. But there is no unifying idea about the region and how it will develop. Many in the region will have wondered, as we did, ‘is that it?’ when the campaign was launched.

Then, in the course of the campaign, there were visits from various senior Labour shadow cabinet ministers. What they all had in common was that none of them talked about Teesside, and none of them talked about their mayoral candidate. All of them used the opportunity to launch new policy initiatives, while Chris McEwan didn’t even make it into the press photos. Were they deliberately trying to snub their candidate?

We don’t think so. We believe they thought that using various towns in the Tees Valley to launch their policy initiatives was promoting McEwan by association. Except that it wasn’t. It just made him look like a spare part.

Earlier this week a leaflet dropped through letter boxes – Vote Labour on 2 May – McEwan’s name wasn’t even on it. It speaks volumes for the party’s attitude to the role of metro mayors. It also harks back to another devolution-related incident, the resignation in 2014 of Johann Lamont as leader of Scottish Labour.

At the time of the incident, Scotland had 41 Labour MPs. A year later it had one.

Johann Lamont’s Stinging Rebuke to Labour

The referendum on Scottish independence in 2014 was not a happy occasion for Labour. It may have been on the winning side, but at the cost of going into partnership with the Conservatives. Many were deeply uneasy about it, and, we think, also acutely embarrassed by the clumsy intervention of Ed Miliband and the shadow cabinet in the campaign. All of this heightened the sense of crisis in Scottish Labour, leading to the resignation a month after the referendum, of its leader, Johann Lamont. At the point of departure, she did not mince her words. Neither did some of her colleagues, who echoed her sentiments. This report is from the BBC:

“Scottish Labour leader Johann Lamont has resigned with immediate effect after accusing the UK party of treating Scotland like a "branch office"…

“Former Scottish Labour first ministers, Henry McLeish and Jack McConnell, spoke to the BBC about the big problems that now faced their party.

“Lord McConnell said he was "very, very angry" and insisted that the UK leadership had serious questions to answer …

“In an interview with the Daily Record, Ms Lamont described some Labour MPs as "dinosaurs" who failed to recognise that "Scotland has changed forever" after September's referendum.

“She told the newspaper: "Scotland has chosen to remain in partnership with our neighbours in the UK. But Scotland is distinct and colleagues must recognise that.”"

Bluntly, the UK party simply could not grasp that Scottish Labour had, and was entitled to, a degree of autonomy now that it had jurisdiction over a devolved part of the UK.

That was ten years ago. UK Labour didn’t get it then and doesn’t get it now. Today, Scottish journalists use it to trip up English Labour politicians (most famously David Lammy in 2022) who still cannot come to terms with the autonomy of Scottish Labour.

That is Labour’s problem. It denies autonomy to people running devolved authorities; it wants those authorities to be run by party apparatchiks; people who spout the party line; people for whom whatever the party wants is what they want. And where the people of a region have experienced something different, the party apparatchik generates little or no enthusiasm among voters who, like those in the Tees Valley, expect something different. It’s why, despite their standing in opinion polls, they lose elections such as those in this region, or at best win by a whisker.

Devolution is not about installing a leader who serves simply as a conduit for Labour Party policy. It’s the lesson that UK Labour seems incapable of learning.