Revealed:

The Untreated

Sewage Capital

of the Tees Valley

The calm before the storm

Scott Hunter

30 October 2021

In the week that the government first refused to make water companies legally responsible for reducing the amount of untreated sewage pumped into the nation’s rivers and seas, then partially backtracked on it, Tees Valley Monitor went in search of the Tees Valley town that is the worst affected by the discharge of untreated sewage.

We began with the Rivers’ Trust, which monitors the pollution in rivers and coastal areas in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and which publishes a helpful map to display its findings. That pollution is the discharge from overflowing storm drains. And here is the map for England and Wales:

source: the Rivers Trust

Water Pollution across England and Wales

The Rivers Trust obtains its data from the Environment Agency. The image shown relates to discharges into water courses in 2020. A couple of things here should be of interest to Johnson’s levelling-up government. While some parts of the south coast show high discharge levels, the highest levels of pollution are in the north, and that by some considerable margin.

As objections to the government’s actions gathered pace across the country, a number of MPs issued statements to explain their actions in which reference was made to the estimated cost renewing the country’s Victorian sewage system. The estimate was that it would cost between £150 billion and £650 billion. Making it a commitment too far.

In this regard, we can’t help but notice a curious feature of the Rivers Trust map, which is how small London’s footprint is compared to cities elsewhere in the country. Someone needs to advise the government that it would be a good idea to investigate the reasons for this discrepancy, and to find out why London’s Victorian sewage system seems to be so much more effective than that of other cities.

Trouble in the Tees Valley

Another aspect of this issue the map of the country reveals is that, the South coast apart, this appears to affect inland areas much more seriously than coastal ones. This is reflected in the Tees Valley. But, before we go any further, we should point out that this situation is not good vs bad, it bad vs worse. No area is exempt. But zoom in on the Rivers Trust map, and the discrepancies between different parts of this region offer some surprises:

source: The Rivers Trust

Look at the beaches south of the Tees and, as is consistent with the national picture, pollution levels are fairly low. On the north side there are two large spots, one which appears to be around Seal Sands and the other at the southern end of Crimdon Dene.

But the main area of concern is the arc of spots in the centre of the map, all of which are in Stockton. When it comes to water pollution in the Tees Valley, Stockton is the loser by a country mile.

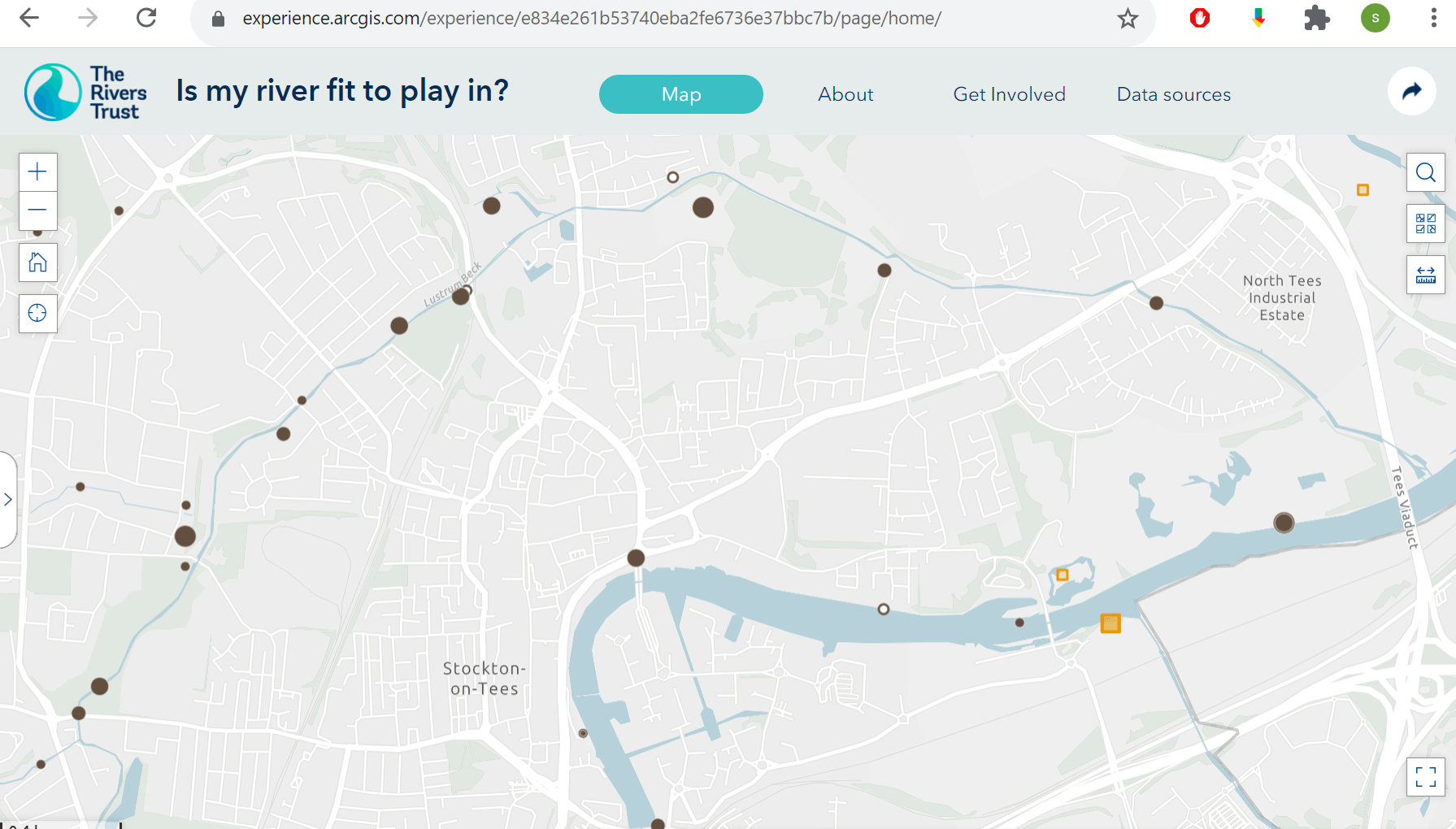

Zoom into that cluster:

source: The Rivers Trust

And we see that all of those discharge points are around Lustrum Beck. Between Oxbridge Lane and Portrack there are thirteen of them. The data compiled by the Rivers Trust shows that these discharged sewage into Lustrum Beck on average 37 times in 2020, for an average of 233 hours. The worst offender was the drain identified as Grays Road:

source: The Rivers Trust

Who Should Take Responsibility?

There is a question that anyone living in the vicinity of Lustrum Beck needs to answer, which is this: Given that a significant proportion of your sewage is dumped directly into a watercourse near you, do you pay less for sewerage than the rest of Northumbrian water’s customers? And the answer is, of course not. No community discount exists.

In a recent court case, Northumbrian Water was fined approximately £700,000 for a pollution incident near Durham in 2017. As the ENDS Report observes,

“The utility company was fined £540,000 and ordered to pay costs of more than £142,000 and a £170 victim surcharge, totalling almost £700,000.”

This raises a question (and we should make clear at this point that we intend no direct criticism of Northumbrian Water, which, by industry standards, is by no means the worst offender in storm water management). Northumbrian Water customers pay for water supply and sewerage services. When that sewerage service does not meet official standards, the company is taken to court and fined. That money goes to the exchequer. But the exchequer isn’t paying for the deficient sewerage service, the water company’s customers are. Are they compensated? (answer: at present only if the effluent actually lands on your doorstep).

storm water drain near Oxbridge Lane, Stockton Lustrum Beck near Bishopton Road, Stockton

If the water companies were faced with the prospect of compensating their customers directly for failures of the quality of service, would they collapse under the strain? It doesn’t look like it. And if they had to fund improvements to the sewerage system, would that bankrupt them? Again, no.

The FT reported on the water companies in 2019, saying that, while they reported £51bn of debt, since privatisation, they had paid shareholders £56bn in dividends. And the reports of debt are themselves suspect, as these companies are each subsidiaries of a nest of other holding companies. The parent company of Northumbrian Water, for example, is Hong Kong-based Cheung Kong Infrastructure Holdings, with a number of holding companies in between, all of whom are likely to extract revenue from Northumbrian Water Group Ltd.

The same FT article points out that no other country has followed the UK’s example in privatising all of its water utilities. Little wonder. What we have is a situation in which Northumbrian Water owns the Kielder Reservoir, but the public owns the sewers. The water companies have a duty to maintain them, but it appears that, if the government is to be believed, the matter of making them fit for purpose goes well beyond maintenance. So, we have a situation where the Cheung Kong Infrastructure Holdings takes the profits, but the public bears the cost.

As for Northumbrian Water itself, in March 2021 it declared operating profit of £195 m and pre-tax profit of £84m:

This may be a good time to write to your MP. The government has now committed to monitoring the situation. This is known as a ‘partial U-turn’. Your MP may be one of those who supports this.

To obtain more information on how to support the Rivers Trust, click here .

Finally, spare a thought for the inhabitants of Seal Sands, who, in 2020 spent 1772 hours swimming in our untreated sewage.